By Steve Sailer

12/30/2018

Sad to learn of the death of a major influence and dear friend, the brilliant and witty psychologist Judith Rich Harris. Too early for an obit, but the NYT review of her magnum opus may be found here: https://t.co/nrqZyHJqMc

— Steven Pinker (@sapinker) December 30, 2018

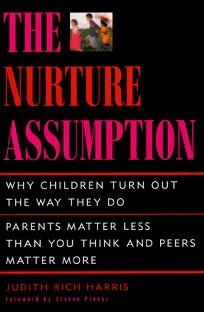

Here’s my review of Judith Rich Harris’s influential book The Nurture Assumption in National Review in 1998:

The Nurture Assumption: Why Children Turn Out the Way They Do.

National Review, Oct 12, 1998 by Steve Sailer

OCCASIONALLY, the Great American Intellectual Hype Machine trumpets a book well worth reading. Even before The Nurture Assumption’s publication, major magazines were ballyhooing Judith Rich Harris’s epiphany. A New Jersey grandmother without academic connections, she had written conventional child- development textbooks that presupposed kids were shaped solely by their parents’ child-rearing style. Suddenly, on January 20, 1994, the scales fell from her eyes, revealing the secret of why children turn out the way they do: “Genes matter and peers matter, but parents don’t matter” (as MIT’s Steven Pinker admiringly summarizes her book in his foreword).

I’m pleased to welcome Mrs. Harris and her impressive rationality, serious scholarship, sardonic humor, and vivid prose to the ranks of realists. Although she tends to tiptoe around the political implications, her analysis of how young people naturally form peer groups that define themselves by excluding others explains why multicultural education, bilingualism, college-admission quotas, busing, and co-ed boot camps perversely worsen race and sex conflicts. Still, her almost Camille Paglia-like ambitiousness drives her to overstate the both the novelty of her true ideas (that genes and peers matter) and the truth of her novel idea (that parents don’t matter).

She’s right that innate differences between children are important, but for experienced parents not befuddled by modern egalitarianism that’s old, even ancient, news. That offspring raised side by side can possess wildly different personalities was clear to well-known parents like Adam and Eve, Isaac and Rebecca, and King Lear. (A second child undermines parents’ belief in their power to mold their children, but child-rearing books hush this up because their market is first-time parents.)

Further, although child-development experts before Mrs. Harris may have failed to understand the power of peer groups, parents always knew. They’ve tried to shield their kids from Bad Influences since long before King Henry IV sought to keep Prince Hal away from “vulgar companions” like Falstaff.

In contrast, her third assertion-that parents don’t matter-is plausible only within her narrow, arbitrary boundaries. To fully explain human behavior, everything matters. Anything conceivable (whether genes, peers, parents, cousins, teachers, TV, incest, martial-arts training, breastfeeding, pre-natal environment, etc.) can influence something (whether personality, IQ, sexual orientation, culture, morals, job skills, etc.).

To show that peers outweigh parents in importance, Mrs. Harris repeatedly cites the work of Darwinian linguist Pinker on how young immigrant children take on the accents of their playmates, not their parents. True, but there’s more to life than language. Not until page 191 does Mrs. Harris admit -in a footnote-that immigrant parents do pass down home-based aspects of their culture, like cuisine, since kids don’t learn to cook from their friends. (How about attitudes toward housekeeping, charity, courtesy, wife-beating, and child-rearing itself?) Not until page 330 does she recall another area where peers don’t much matter: religion! Worse, she never notices what Thomas Sowell has voluminously documented in his accounts of ethnic economic specialization. It’s parents and relatives who pass on both specific occupations (e.g., Italians and marble-cutting, Cambodians and doughnut-making) and general attitudes toward work, thrift, and entrepreneurship.

Nor can peers account for long-term social change among young children, such as the current switch from football to soccer, since pre-teen peer groups are intensely conservative. (Some playground games have been passed down since Roman times.) Even more so, the trend toward having little girls play soccer and other cootie-infested boys’ sports did not, rest assured, originate among peer groups of little girls. That was primarily the idea of their dads, especially sports-crazed dads without sons.

Although millions of parents sweat and scrimp to get their kids into neighborhoods and schools offering better peer groups, Mrs. Harris redefines this as merely an “indirect” parental influence. She claims modern studies can’t find predictable relationships between “direct” influences (i.e., different child-rearing styles) and how children turn out. But that may reflect an inherent shortcoming of these necessarily non-experimental analyses. For example, she asserts (not necessarily reliably) that studies prove it doesn’t matter whether mothers work or not. But the same methodology would report that it doesn’t matter whether you buy a minivan or a Miata, since purchasers of different classes of vehicles report roughly similar satisfaction. In reality, women don’t randomly choose home or work; they agonize over balancing career and family. They tailor their family size to fit their career ambitions and vice versa. Mothers will then readjust as necessary, looking for the compromise that best meets their particular family’s conflicting needs for money and mothering. For instance, a working mother might quit when her second baby proves unexpectedly colicky, then return when the children enter school, then shift to part time after her husband gets a big raise. This non-random behavior of moms is bad for these studies, but good for their kids.

And why do mothers care so much? Disappointingly for a Darwinian, Mrs. Harris blames it on The Media. She hopes her book will encourage parents to fret less, but it is unlikely to have much impact on mothers, since natural selection has crafted them so that, as the old saying puts it, “‘Worry’ is a mother’s middle name.” In contrast, men will find her theory more appealing, with painful consequences not just for their kids, but for themselves and all of society. Crime and poverty follow when a culture fails to persuade men that “fathering” requires decades rather than minutes.