11/25/2021

If there is anything New York Times subscribers like more than reading about bad white people being systemically racist, it’s endurance sports. As I’ve often pointed out, while anaerobic exercise like weightlifting correlates with right of center politics, aerobic exercise correlates with NYT subscribers’ politics. (How causal is this correlation deserves research.) So the NYT publishes a huge number of esoteric articles about running techniques and the like.

Ever since blacks took over traditional American sports like football and basketball and Kenyans started winning the gold medals in the traditional American sport of distance running, white American have been inventing new endurance events that even Kenyans can’t beat them at, such as the triathlon, which combines marathoning with long distance swimming and bike riding.

So this provides a tricky challenge for an NYT reporter, who does a pretty good job of servicing subscribers’ psychic needs.

From The New York Times sports section:

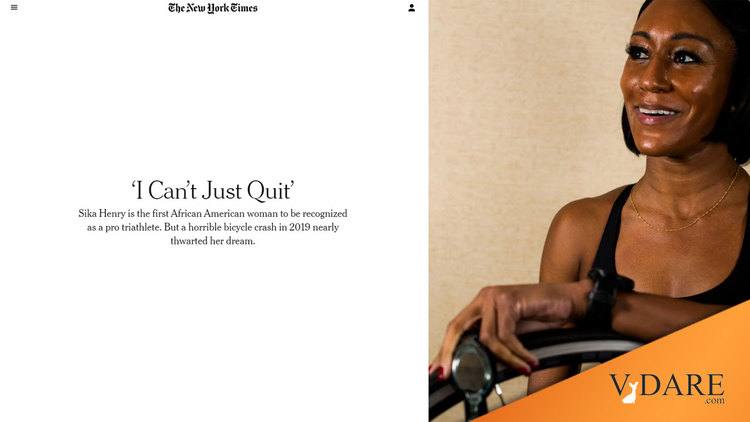

Sika Henry is the first African American woman to be recognized as a pro triathlete. But a horrible bicycle crash in 2019 nearly thwarted her dream.

The famous Ironman Triathlon that emerged in Hawaii a few decades ago consists of a 2.4 mile ocean swim, a 112 mile bike ride, and a full Marathon 26.2 mile run. There are also shorter, less crazy versions, but each of the three events falls well into the endurance rather than sprint spectrum.

By Alanis Thames

Nov. 23, 2021As Sika Henry worked to become the first female African American professional triathlete, she remembered her childhood conversations about race with her family.

Her parents told Henry and her brother, Nile, stories about their paternal grandfather, who was a track and field athlete and football player in the 1920s. Because of segregation, he was not allowed to play in the N.F.L., and instead pursued a career as a jazz musician.

Just think of all the white football players who got rich playing in the NFL in the 1920s, such as Red Grange and, uh, … uh … Bronko Nagurski! … Oh, I guess he only played in the 1930s. Never mind. But, the point is, great-grandpa might have been as good as Red Grange. And that white people back then were bad.

This memory stuck with Henry. She uses it as motivation in her journey in triathlon, a sport in which few contestants look like her.

“He said to my dad one day, ‘I never thought I’d see the day when Blacks could play professional sport,’” Henry said.

And at times, Henry didn’t know if she would ever compete professionally in her sport, either.

No other African American woman had earned an elite license — which gives triathletes their professional status — in triathlon before Henry, according to U.S.A. Triathlon, the sport’s national governing body. She overcame a horrible bicycle crash during a race in 2019….

Henry used to hate distance running. She walked on to the track and field team at Tufts University, a Division III school outside Boston, where her main event was the high jump on top of racing in the 200-, 400- and 4×400-meters. To train for the 400, Henry’s coach suggested that she run three miles sometimes during the week. She would balk at the distance. “I thought that was just so long and painful,” Henry said.

In 2013, though, a breakup left her seeking a distraction, so she signed up for a local sprint triathlon, a beginner friendly race consisting of a half-mile swim, a 12.4-mile bike ride and 3.1-mile run. …

And yet Henry noticed there were almost no other Black people competing alongside her.

“I was just like, ‘Where are they?’” she said.

While other individual sports, like sprinting, have large numbers of African American competitors, triathlon draws little nonwhite participation.

The two words “like sprinting” are a dog whistle to HBD-aware triathletes that the reporter isn’t a total ignoramus, that she knows that blacks of West African ancestry tend to be much better at short than long distances. But it’s not going to disrupt the average NYT subscriber’s reading of this as a nice story about a black person heroically triumphing over the systemic racism that keeps blacks from winning their rightful share (i.e., virtually all) of triathlons.

As of this year, U.S.A. Triathlon said, 13.3 percent of its annual members are people of color. Less than 2 percent are Black or African American.

“It’s kind of taboo,” said Dr. Tekemia Dorsey, the only Black female board member of U.S.A. Triathlon.

“You’re not going to go to an urban community and see a race or have an opportunity to race,” Dorsey said. “You might go 30 miles north, east, south or west in a rural or suburban area, and you have triathlon races all over the place. So for minorities, that’s still part of the barrier.”

Henry is only the second Black triathlete in the U.S. to reach professional status. Max Fennell became the first African American triathlete to earn his professional certification in 2014.

During her quest to gain professional status, Henry garnered a sponsorship from the shoe company Hoka in a rarity for amateurs in endurance sports.

In other words, the Establishment wants more black triathletes, but blacks aren’t that interested. The rest of the article, read carefully, is about how much support she has received from the triathlon community despite not being all that good.