07/21/2022

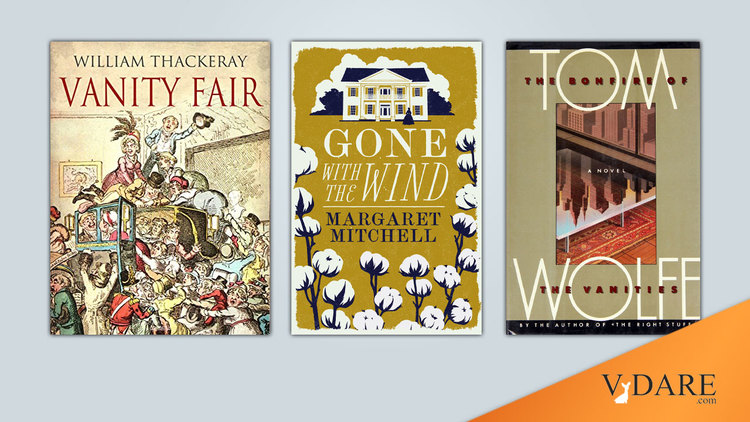

I finally finished reading the 1848 novel Vanity Fair. A few comments:

It’s extremely enjoyable. Despite a fairly rambling plot covering almost 800 pages from roughly 1813 to 1828, it’s a page-turner because the characters and situations are interesting enough that you want to find out what happens.

I’d describe Vanity Fair as the precursor to Gone With the Wind, in that it centers around two young women, the nice but mopey Amelia (the precursor of Melanie Hamilton, played by Olivia De Havilland) and the not nice but more interesting Becky Sharp (Scarlett O’Hara, played by Vivien Leigh). In Gone With the Wind, Melanie expostulates:

“I fear I cannot agree with you about Mr. Thackeray’s works. He is a cynic. I fear he is not the gentleman Mr. Dickens is.”

The male characters in both tend to be army officers who go off to a big battle, Waterloo in VF and Gettysburg in GWTH.

Overall, I’d say that GWTH is the new improved VF, with more memorable characters and settings. Margaret Mitchell always denied having read Vanity Fair, but Gone With the Wind sure seems like a punched-up version of Vanity Fair, with Mitchell raising the stakes wherever Thackeray was inclined to let them ride.

For instance, while the British win at Waterloo and so English society mostly goes on as before, the Southerners lose at Gettysburg and soon the old society is, like the title says, gone with the wind. The Southerners need to learn a lot of hard new lessons about life. Melanie and her husband Ashley Wilkes fail to adapt to the new world, while Scarlett, despite her self-centered sense of entitlement and general knuckleheadedness, eventually succeeds.

In contrast, from the first page of Vanity Fair, Becky Sharp, a poor orphan, is smarter than the rich people around her. Thackeray points out near the beginning of the book that when she claims to love children, she would soon learn not to make claims so easily disproved. “The little adventuress” seldom learns over the 800 pages because she was already supremely worldly wise from a tender age.

In contrast to Scarlett, Becky is always rational to the point of being cold-blooded. Becky wants material comfort and to rise in status, but she lacks particular passions (until late in the book when she starts to develop a gambling problem). She has no Ashley Wilkes to pine over.

Indeed, Becky is so reasonable that she often behaves surprisingly nicely to the other characters because, having calculated all the factors, she doesn’t see how it could cost her much.

And Mitchell takes Thackeray’s admirable but stiff Captain Dobbin, who is lovelorn over Amelia, who foolishly ignores him throughout, and turns him into the pirate king Rhett Butler (Clark Gable), who instead of being lovelorn over Melanie is lovelorn over Scarlett. This creates the 20th century’s most popular fictional couple.

Vanity Fair, which was published in serial form on newsstands from 1847-1848, gives the impression that Thackeray didn’t work on it all that hard, although I suspect that’s misleading. The plot of Vanity Fair doesn’t come together as brilliantly at the end as its inspiration, Fielding’s 1751 novel Tom Jones, does. Still, nobody can write something this good without a lot of effort.

Vanity Fair is also an inspiration for Bonfire of the Vanities by Tom Wolfe , who may have been misled by Thackeray’s air of ease into thinking this novel-writing thing wouldn’t be so hard to pull off. So, Wolfe signed up with great publicity to publish Bonfire serially like a Victorian novelist in Rolling Stone. But his first draft wasn’t very good, so he had to do a lot of hard work making major changes before the book form was published.

Status and money, for instance, are explicitly explored in both Vanity and Vanities, although Thackeray set his stories a few decades in the past, so I’m not sure how relevant the salaries and prices were to 1848 readers, while Wolfe used current mid-1980s prices.

A big difference is that VF is about two-thirds a women’s novel, while Bonfire is very male oriented. Wolfe had started out in the 1960s quite adept at profiling young women in his early journalism, but that faded during his Right Stuff era.

One thing I noticed again in reading Vanity Fair about English society is that up to a certain point in the 19th century, you could get very rich in positions of authority with nobody questioning it. For example, Amelia’s brother Joseph is a tax collector for the British East India Company and has gotten very rich at it. (Obviously, the chance of dying of fever in India was quite high, which was some justification for the lavish fortunes made there.)

The English liked giving large financial rewards to people who succeeded in positions of authority. For example, John Churchill was rewarded for winning the War of the Spanish Succession with a Dukedom and the promise from Parliament of 250,000 pounds, enough to get started on building a 300,000 square-foot palace at Blenheim. About the last example I can remember of this is General Douglas Haig being granted 100,000 pounds after the Great War. After WWII, in contrast, Field Marshall Montgomery got many honors but little cash.

England had kind of a piratical culture (as illustrated in the Aubrey-Maturin novels by the incentives given Royal Navy captains to capture enemy shipping). And then at some point in the 19th century, the culture shifted to expecting officials to do their duty for a standard salary, with no huge bonuses or opportunities for peculation.

You can see the shift starting to happen in Anthony Trollope’s 1855 novel The Warden. A nice old Church of England cleric has a sweet setup that becomes the target of a Victorian cancel culture mob led by Charles Dickens (“Mr. Popular Sentiment”) and Thomas Carlyle (“Dr. Pessimist Anticant,” which would be a great pseudonym for Curtis Yarvin).

You see, way back in the middle ages, a philanthropist had donated donated some acreage to support 12 elderly fieldhands in an almshouse, with a house for the warden of the almshouse, who is appointed by the Bishop of Barchester. But over the centuries, the town of Barchester has expanded and the former fields are now houses and throw off a lot of rent annually. Nobody has thought to increase the number of old men supported, so the annual income above what is needed for their support now keeps the warden and his daughter living in quite a bit of luxury.

For decades, indeed, for centuries, this sinecure had been fine with everybody. Of course, the feeling was, the warden of the almshouse should live in style like a gentleman should. Suddenly in mid-Victorian times, however, Mr. Sentiment and Dr. Anticant are getting Parliament up in arms over the scandal.

You can see this change in the standard of living allotted to the Prime Minister and ex-PMs. When my wife met Mrs. Thatcher in 1999, she noted that her dress had been mended with needle and thread in at least two places.

Serving Prime Ministers have had a very nice weekend country estate, Chequers, for the last century. But No. Ten Downing Street is cramped and there are all sorts of cheapskate restrictions. In the TV show The Crown, there are a couple of scenes of Mrs. Thatcher cooking dinner for her cabinet in No. Ten Downing Street’s small kitchen with her daughter enlisted as scullery maid, (The cabinet was there to discuss party business, so dinner was on the PM’s shilling.) Anytime a PM wants to redecorate No. Ten, it becomes a scandal in the tabloids.

Characteristically, the key scandal that brought down Boris Johnson was him spending 15 minutes with his staff during lockdown at a pizza party.

Some of this is of course the distinction between Head of State (the monarch, who still lives in the grand style) and Head of Government. But much of it goes back to the Victorian shift away from the English thinking like pirates. It’s hard to understand European history without realizing that Continentals tended to see the English as a pirate kingdom of offshore raiders.

Can’t load tweet https://x.com/toad_spotted/status/1550051849331417088: Sorry, that page does not exist

In Evelyn Waugh‘s novels, every young man of fashion owes a fortune to his tailor but is putting off the day he’ll have to go butter up his disapproving father to get him to pay off his tailor.

It seems as if tailors and landlords in pre-WWII England had to stay up on society gossip over whether their customers and tenants still had good prospects of inheriting fortunes someday or whether they had fallen out of favor with their rich elderly relatives. Becky Sharp and her husband, a baronet’s son, live like lords on debt for a number of years despite little income beside what Becky’s husband can win as a poolshark and cardsharper. But small businessmen were willing to bet that their knowledge of the Crawley family inheritance dynamics was accurate enough to guesstimate that they’d eventually be bequested enough to pay off their landlord and victualers without having to flee to Europe to avoid debtor’s prison (with the accompanying ruination of their small creditors).

Life was full of interest back then. People gossiped about the doings of the rich and fashionable not just for the fun of it, but because aristocratic family gossip was crucial business intelligence.

The public need to exchange detailed information about which member of society was likely to inherit how much and what threats were posed by new developments with his family likely contributed to the writing of The Way We Live Now–style novels. Nowadays, fewer local businesspeople are at risk of local celebrities defaulting on their debts rather than defaulting to banks, so I’m not likely to hear through the grapevine that, say, Angelina Jolie’s creditworthiness is increasingly doubtful because she’s alienated both Brad Pitt and Jon Voight. Whereas Thackeray probably heard juicy stories like that every day.